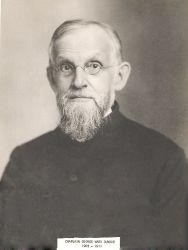

Chaplain George Ward Dunbar

A Biographical Sketch

Extracted from an article by The Reverend Arthur Mavrode, OC, entitled Fort Concho Chaplians

The West Texas frontier in the 1870s was a wild and dangerous place. There

was little law enforcement and Indian depredations had caused widespread terror

among the settler population. In order to bring a semblance of stability to

the region, the federal government established a line of frontier forts in the

post Civil War period. The challenges were of course enormous. Incredible

extremes in weather, isolation, frequent Indian raids, bandits, and racial

tensions caused by the imposition of military law and order by Buffalo Soldiers

on a defeated population of a Confederate state made the situation impossible.

Such was the environment in which Chaplains of the United States Army

ministered... George Ward Dunbar was born in Moravia, New York in the year 1833. A

registered Son of the American Revolution, his Great Grandfather who was of the

Jewett clan of Lyme, New York was killed in the war of independence when

according to Bancroft: "Among the Jewett of Lyme, Captain of Volunteers

was run through the body by the officer to whom he gave up his

sword." Dunbar attended Hobart College of Geneva, New York in 1855 and was

graduated valedictorian of his class. He then went on to his

seminary studies, attending the general Theological Seminary of the Protestant

Episcopal Church in New York City, and graduating from there in 1860. On

July 1, 1860, he was ordained and went on to minister parishes in New York,

Minnesota, and Wisconsin. It was while serving as Rector of Christ Church in Janesville, Wisconsin

that he answered the call to serve as a Chaplain in the United States

Army. He was commissioned as an officer in 1876 and served in his career

in Texas, Dakota, California, and Virginia. It should be noted that Army Chaplains in these frontier forts were also

expected to supervise the post education program, administer the post treasury,

serve as post librarian, manage the post bakery and supervise the maintenance

of the post garden. There would be great frustration for the chaplains as

supplies were always slow to arrive and there never seemed to be enough funds

to carry on any effective education program. Adding to the frustration Chaplain

Badger found himself often at odds with the newly assigned post commander

Colonel Benjamin H. Grierson. Colonel Grierson, a hero of the Civil War,

expressed his feelings concerning Chaplain Badger in a letter he wrote to his

wife after Badger had died on post and after receiving word that Chaplain

Dunbar would replace him: "I am sorry that this Chaplain Dunbar has not

a loud call to go somewhere else… but the powers that be have ordered him here

possibly because this is a chaplain's post or may be on account of the supreme

wickedness of this locality. He will be good to occupy the quarters and

eat commissary stores and to attend strictly to every body's business but h is

own. I hope he will succeed in saving a great many souls, his own

included." Grierson's remarks not only reflected his opinion toward Badger but toward

all chaplains. Fortunately, when Dunbar arrived at Fort Concho, he did

make a favorable first impression on his commander. After attending a

Sunday morning service, the colonel again wrote to Mrs. Grierson: "The Chaplain preached quite a good

sermon. He has an easy delivery, and set forth some plain, sensible,

conservative, democratic, religious ideas in an effective agreeable

manner. He is to preach tonight again, more especially for the soldiers

and colored people. There were a good many soldiers present today.

He, the Chaplain, takes hold of matters as if he was determined to put forth

his very best 'endeavor' to make himself useful in every possible proper way

and I am rather inclined to think that he will be quite successful. A new

broom is apt to sweep clean for a time, however, and he may hereafter get to

playing the Old Soldier." Though Grierson's comments reflected unfavorably upon Badger by comparison,

others thought differently. In the summer of 1871 the post surgeon made

an entry in his monthly record that Badger was "very zealous in every

duty" and managed the post garden efficiently. " There were probably many letters and reports sent by the Chaplains of

Fort Concho to both their military superiors and Bishops. Regrettably,

few have survived. Chaplain Dunbar wrote a number of reports during his

tenure at Fort Concho. Fort Concho, Texas, May 15, 1877 To the Rt. Rev. E.R. Wells, S.T.D., Bishop of the Diocese of Wisconsin

I have the honor to report, that after the resignation of the Pastorate of

Christ Church, Janesville, in consequence of my acceptance of a Post

Chaplainship in the U.S. army, which occurred in September last, I came at once

to this post, where I have ever since remained, in the steady performance of

such duties as appertain to my office. I hold services on Sunday morning,

for the officers and their families, and on Sunday evenings, for the men.

On the evenings of the week, I hold night-school for the soldiers. I have

married three couples; buried four soldiers, and three persons not belonging to

the post.

Very respectfully, your obedient servant,

G. W. Dunbar In the following year, Chaplain Dunbar issued the following report: Fort Concho, Texas,

June 11, 1878 To the Rt. Rev. E.R. Wells, S.T.D., Bishop of the

Diocese of Wisconsin

My Dear Bishop: Since my last annual report I have been constantly at

this post. The hardest work of any army Chaplain is usually the

teaching. This is likely to be increased by a recent order, which makes

the chaplain the Principal of a school, which shall include soldiers, children

at the post, and citizens' children. His only assistants are to be

detailed soldiers.

Besides this he must visit the sick, bury the dead (too often murdered dead);

hold his Sunday services (usually in an airy ward of the hospital); and write

his sermons – fifteen minutes should be limit of the longest.

Then he must usually act as Post Treasurer, and superintend and be responsible

for library and reading room. These duties to say nothing of taking ones

turn on Boards of Survey and Receiving Boards, show that the life of an army

Chaplain cannot be the life of luxurious idleness that some have pictured it.

Yours in the Church of Christ, G.W. Dunbar

Post Chaplain, U. S. Army In February 1879, Chaplain Dunbar reported to the Adjutant

General. It was that year the new post chapel/school was

constructed: Sir: I have the honor to report that I

passed the month of February in the performance of my duties at this post. A post school was formally established Feb.

22 and placed under my charge. The new schoolroom is about 40 by 20 and

is by far the best finished room in the post. A very promising teacher

was found in Sergeant Howell, of Co. A, 25th Infantry. He is

very patient, and very ambitious and will in due time become an excellent

teacher. [note: Sgt. Howell was a Buffalo Soldier] In the children's department of the school,

only the children of Officers and employees, 21 in number, have so far been

admitted. The studies pursued are reading, spelling, writing, arithmetic,

geography, and U.S. history. The children's hours for school are from 9:30

to 1 p.m. The school for enlisted men is held from

retreat to tattoo. Some 45 men have attended the school. The

studies, so far, are reading, spelling, writing, and geography and U.S.

history. Arithmetic will be added as soon as we can get desk and slates. Very Respectfully,

your Obedient servant, G.W. Dunbar, Post

Chaplain, USA Chaplain Dunbar's last known report to his Bishop

while serving at Fort Concho:

I have spent the year which has elapsed since the last session of the Diocesan

Council, in the performance of the usual multifarious duties of a post

chaplain. A little preaching and a good deal of teaching. A little

watchfulness concerning the old leaven of sin, and a good deal with regard to

that which enters into the soldiers' rations. Much secular work without wholly

neglecting the pastoral – such is my daily record.

I regret to say, that the state of my health for the past year, has been such

as to make it impossible to speak or read at any length in a standing position,

so that I have been compelled to very much abridge my Sunday services.

I have obtained a leave of absence for five months, beginning with

to-day. This will bring me to Wisconsin just too late to attend the

Council. My address during the summer will be Janesville, Wis. Chaplain Dunbar's service to Fort Concho would

indeed end that summer but not his service to his God, or to his country.

One can sense the toll the chaplain's ministry could take on the

individual. I can say with confidence and joy that most of those who

respond to God's calling to ministry do so with great zeal. I believe

Chaplains Badger and Dunbar were no different. From what I know of

Chaplain Dunbar in his days of ministry prior to his Chaplaincy, the settings

of his assignments were typical of parish life of the time. Nothing very

unusual and not fraught with danger or many secular issues. Could Chaplain Dunbar ever have been prepared

for…. The isolation of a frontier fort? The lack of adequate supplies? The racial tensions brought about by the

introduction of Buffalo Soldiers to a defeated Confederate people and

land? The harsh environment scotching Texas summers or

fringed winters? The lack of a place to worship or to teach? The lawlessness of the small town across the river

known as Saint Angela were prostitution and murder were rife? The many duties that were not normally expected of

a pastor in a civilian parish but were now demanded of his chaplaincy? In one sense I don't believe that anyone could have

been prepared for this – but then again, God often calls us to places we may

not want to go or people whom we may not wish to deal with. I can say that with this brief insight into

the life of army chaplains in the western frontier, I have come to a great

appreciation of what the calling to ministry truly entails. Sacrifice,

fearlessness, perseverance, hope and most of all faith ruled their lives during

these most difficult times. Their ministry should never be forgotten, but

remembered and told for generations to come. Arthur J. Mavrode+ Chaplain, Fort Concho National Historic

Landmark [i]

James T. Matthews, “Fort Concho” 2005, Pages 47-50 A good deal of the information contained in this paper was derived from a

number of archival collections. A major portion of the information came from

an excellent book on Fort Concho written by James T. Matthews. You can find

more information about this book by going to the following link: http://www.tamu.edu/upress/BOOKS/2005/matthews.htm